Jörn Vanhöfen

-

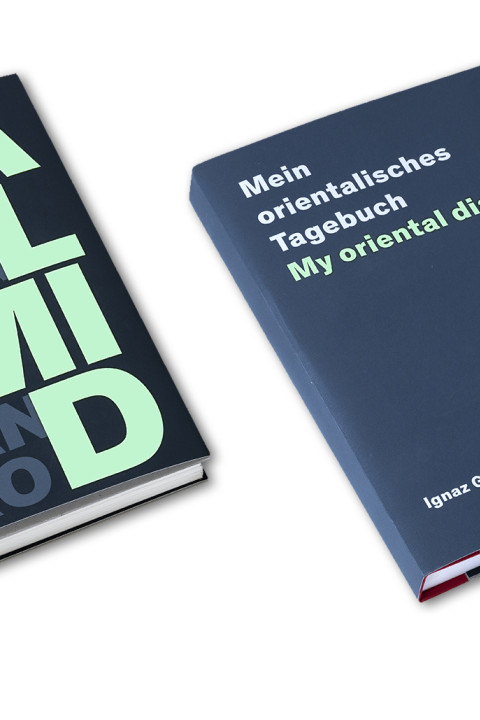

TALMIDBitter Edition Berlin, 2021

TALMIDBitter Edition Berlin, 2021Jörn Vanhöfen

TALMID

two artists books:

TALMID (with photographs by Jörn Vanhöfen)

MEIN ORIENTALISCHES TAGEBUCH (reproductions from a travel diary by Ignaz Goldziher)

with a text by Navid Kermani

German/Englisch

40 photographs as giclèe print on Japanese washi paper

handbound

Edition: 10 + 124,5 x 32,5 cm

Bitter Edition Berlin, 2021

Euro 1800,00 -

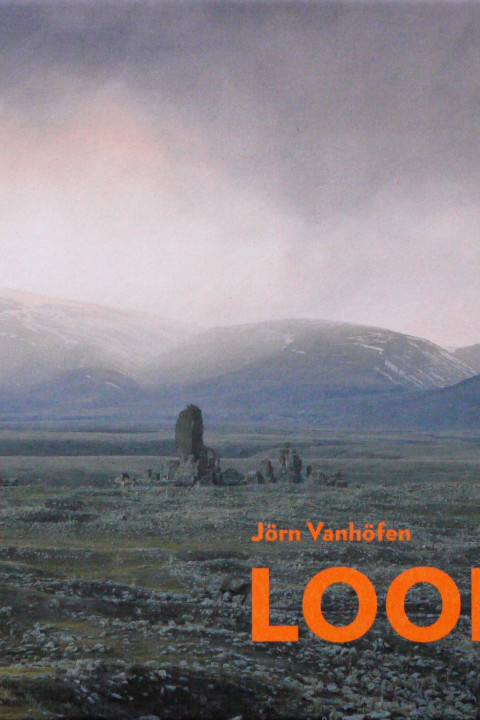

LoopKuckei + Kuckei, 2015

LoopKuckei + Kuckei, 2015Jörn Vanhöfen

Loop

Vanhöfen's pictures bear witness to the metamorphosis of material; to both small and gigantic upheavals. The melting of the glaciers cannot be prevented, not even by cleverly applied layers of insulation. Areas of the earth are now being exposed that were covered for thousands of years. New continents make their appearance while vast tracts of coastline are about to vanish from the map. But this future is not an apocalyptic vision, but rather a vision of Nature that will inevitably re-conquer its domain in some future post-human era.

58 pages

24,5 × 27,5 cm

Kuckei + Kuckei, 2015

ISBN 978-3-00-047796-6

Euro 25,00 -

AftermathHatje Cantz, 2011

AftermathHatje Cantz, 2011Jörn Vanhöfen

Aftermath

Photographer Jörn Vanhöfen (*1961 in Dinslaken) travels the world to capture images of areas that are undergoing rapid change. They are always places where people believe wholeheartedly in permanent growth and limitless profit, for the consequences of this fatal attitude are the objects of his photographic work. Vanhöfen journeys to Africa, Europe, Asia, and North America, going wherever the results are demonstrably obvious—from the Chicago stock exchange, the townships of Cape Town, and the scorched forests in Apulia to abandoned factories in Detroit and salvage yards in his hometown in the Ruhr region. His unique, poetic photographs depict ruins of our time. And while they may be fascinatingly beautiful, the looming consequences of our actions at the same time horrify us.

148 pages

34,8 × 28,9 cm

Hatje Cantz, 2011

ISBN 978-3-7757-2975-8

Euro 58,00

Jörn Vanhöfen was born 1961 in Dinslaken, Germany. Studied from 1985-1988 at Folkwang Schule, Essen and from 1989 – 1993 at the Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst, Leipzig. Jörn Vanhöfen lives and works in Berlin.

Solo Shows

-

2016

Zwischenzeit: 1989 – 1991, Kuckei + Kuckei, Berlin, Germany

Loop – Jörn Vanhöfen, Museum Haus Ludwig, Saarlouis, Germany

-

2015

Jörn Vanhöfen – Loop, Alfred Ehrhardt Stiftung, Berlin, Germany

Jörn Vanhöfen – Loop, Opelvillen, Rüsselsheim, Germany

-

2014

Jörn Vanhöfen – Aftermath, FO.KU.S – Foto Kunst Stadtforum, Innsbruck, Austria

Beyond Eden, Galerie Roemerapotheke, Zurich, Switzerland

-

2013

Disturbia, Kuckei + Kuckei, Berlin, Germany

Grenzenlos, Kunstverein Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany

-

2012

Aftermath, Robert Mann Gallery, New York City, NY

-

2011

Kuckei + Kuckei, Berlin, Germany

-

2010

Die Elbe, Oldenburger Landesmuseum, Oldenburg, Germany

-

2009

Aftermath, Kuckei + Kuckei, Berlin, Germany

-

2008

Galerie Römerapotheke, Zurich, Switzerland

-

2007

Aftermath, Kuckei + Kuckei, Berlin, Germany

-

2006

Kulturhaus Osterfeld, Pforzheim, Germany

-

2005

K. Galerie, Lissabon, Portugal

-

2004

Galerie Römerapotheke, Zurich, Switzerland

-

2001

Kunstverein Glückstadt, Glückstadt, Germany

Altonaer Museum, Hamburg, Germany

-

1998

Altonaer Museum Hamburg, Germany

Kulturhaus Aalen, Aalen, Germany

-

1997

Instituto Cervantes, Rome, Italy

-

1996

Instituto Cervantes, Bremen, Germany

Museum Velbert, Velbert, Germany

Habana Vieja, Göttingen, Germany

-

1995

Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, Germany

-

1994

Centro Cultural Jose Marti, Mexico City, Mexico

Goethe Institut, Mexico City, Mexico

Universität Monterey, Monterey, Uruguay

-

1993

Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst, Leipzig, Germany

Fototeca de Cuba, Havanna, Cuba

Group Shows

-

2017

The Wall, Podbielski Contemporary, Berlin

-

2016

Accrochage +, dr. julius | ap, Berlin, Germany

-

2014

Am Ende der Sehnsucht – Fotografische Positionen zu Tod und Meer, kunst:raum sylt quelle, Rantum / Sylt, Germany

-

2013

Obscure, Villa Renata, Basel, Switzerland

Am Ende der Sehnsucht – Fotografische Positionen zu Tod und Meer, Altonaer Museum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte, Hamburg, Germany

-

2012

Lost Places – Orte der Photographie, Galerie der Gegenwart, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, Germany

Bildspuren – Unruhige Gegenwart, 7. Darmstädter Tage der Fotografie, Darmstadt, Germany

-

2011

Leipzig.Fotografie / 1839-2011, Museum der bildenden Künste, Grassi Museum für Angewandte Kunst und Stadtgeschichtliches Museum, Leipzig, Germany

-

2010

10 Jahre Kunstverein Glückstadt, Palais für aktuelle Kunst, Glückstadt, Germany

HomeLessHome, Museum on the Seam, Jerusalem, Israel

-

2009

Nation and Nature, Museum on the Seam, Jerusalem, Israel

-

2007

… und grüßen Sie mir die Welt/fotografierte Heimaten, Stuttgart, Germany

Weather Report, Centro Atlantico de Arte Moderno, Las Palmas, Canary Islands

-

2006

Kunstsalon, Berlin, Germany

-

2005

Berlin Photographers, Rencontres de la Photographie, Aix-en-Provence, France

HKM Projekt in Zusammenarbeit mit der Stiftung Wilhelm Lehmbruck Museum, Duisburg, Germany

-

2003

Teutonen Pop, Stanford University, CA

-

2000

Östlich von Eden, Kasseler Kunstverein, Kassel, Germany

Goethe Institut, Mexiko City, Mexico

Centro Cultural Aleman, Monterrey, Uruguay

Haus der Geschichte, Bonn, Germany

-

1999

Östlich von Eden, Postfuhramt Berlin, Berlin, Germany

-

1998

Augenzeugen, Goethe Institute in Rome, Madrid, Helsinki, Mexiko City, Barcelona, Paris, Seoul, Tokio

-

1997

Willy Brandt Haus, Berlin, Germany

-

1993

100 Jahre Photographie in Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany

-

1992

Turning Points. East German Art in Revolution, Sunderland, Carlisle, Aberystwth, Sheffield, Bradfort, Newcastle, London, Great Britain

Kunstverein Heilbronn

Leipziger Schule, Castrop Rauxel, Germany

-

1990

Gallery Kuba, Tokio, Japan

-

1989

Gerrit Academy, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Public Collections

-

Art Gallery of Ontario

The Progressive Art Collection, OH

Landesbank Baden-Württemberg, Stuttgart

HessKiss Collection, Zurich

AXA – Winterthur, Art Collection, Zurich

Museum on the Seam, Jerusalem

Jerry Speyer Art Collection, New York